Elvis Broke Fashion Boundaries, Too

The New York Times, June 2022

He was many things, as a new biopic illustrates, but one of the least appreciated was his role as a gender pioneer.

Everybody has a personal Elvis. He is there for us all, lodged in the collective unconscious, one of few humans who can legitimately be termed an icon, although it is not always certain of what.

There is musical Elvis and race-reckoning Elvis and sex symbol Elvis and Las Vegas Elvis and Mississippi Elvis and rockabilly Elvis and Hollywood Elvis and Warhol Elvis and imperial Elvis and impersonator Elvis. There is, too, cautionary Elvis: the bloated, pill-addicted burnout dead at 42.

There is foremost Elvis, the legend, a man whose humble origins and meteoric rise have been rehearsed so often the details hardly seem to describe a human that breathed the same air as the rest of us. Resurrecting that figure is no easy task, and so, for many, the Elvis in Baz Luhrmann’s dreamily overwrought historical biopic “Elvis” will inevitably fall short. How could it not? To capture Elvis is like describing a quasar — a remote and intensely luminous object from an early universe.

It has been four and a half decades since Mr. Presley’s death, nearly 87 years since he was born in a modest frame house in Tupelo, Miss. Yet somehow he remains as potent a figure as ever. He is instantly identifiable and simultaneously obscure, a symbol of the working-class South he emerged from; a pop world he transformed; a culture of erasure that even now leaves in doubt how much of Elvis was his own creation and how much borrowed from the Black culture that is still the barely acknowledged American mother lode.

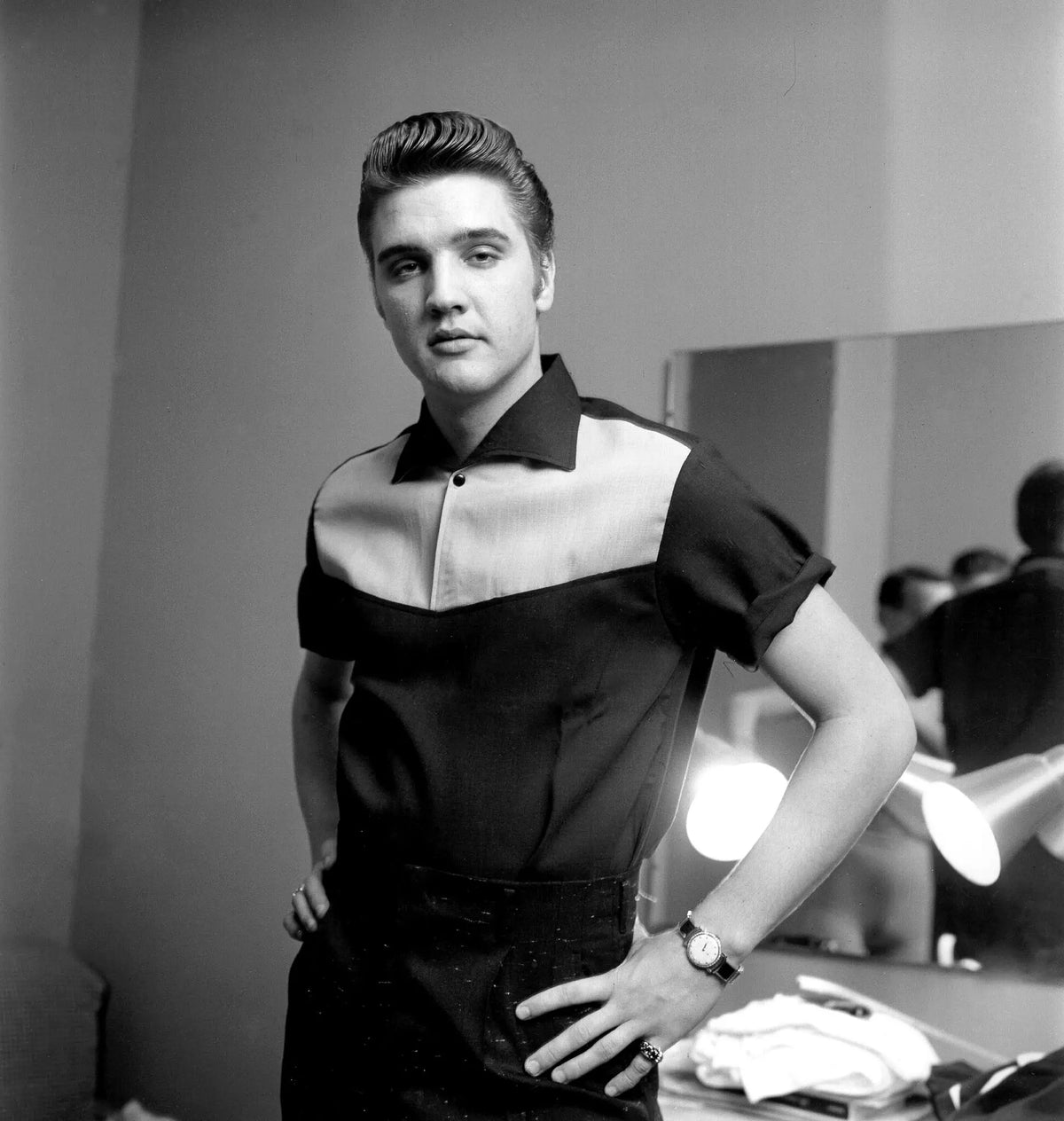

There is, more simply, Elvis, a creature of style and fashion — and that Elvis should be easiest to pin down. Yet even here Elvis remains tantalizingly elusive, the person inside the clothes clinging stubbornly to his mystery. Although we cannot know with much certainty how Elvis arrived at and evolved his indelible image, at least we can track what he wore.

In the beginning there were surprisingly conservative stage suits and jackets cut fuller than was the custom of the ’50s, although less for reasons of style than to accommodate Elvis’s the Pelvis’s scandalous gyrations.

As his fame grew and club dates became arenas, visibility demanded of him greater flamboyance. One result was an all but radioactive gold lamé suit his manager Colonel Tom Parker commissioned from the rodeo tailor Nudie Cohn that was featured on the cover of the 1959 album “50,000,000 Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong.”

Anyone who has ever visited Graceland knows that Elvis’s domestic tastes — Jungle Room aside — tended more to bourgeois gentility than his public image would suggest. True, he owned a lot of flashy cars (by some accounts more than 260 over his brief lifetime), a private jet and had a penchant for diamond-encrusted gumball rings and pendants (most famously with his Taking Care of Business logo, TCB).

But the get-ups we most often associate with him, and that have influenced artists as unalike as Tupac Shakur, Bruno Mars and Brandon Flowers and continue to inspire, if that is the word, designers at labels like Versace, Cavalli, Costume National and Gucci, were a far cry from the bathrobes Elvis lounged in at home.

If that lamé suit, more than any other single garment, argued a case for Elvis as a sartorial rebel, pushing the limits of convention in a Brooks Brothers era, when lines of demarcation between the sexes were clearly drawn, it was unquestionably his pompadour that established him as a gender radical. American men in the monochrome Brooks Brothers ’50s did not wear shiny gold suits. Assuredly, they did not dye their hair.

Yet under the clear influence of Black musicians like Little Richard, whose teased bouffant tresses even today look radically, daringly queer, Elvis not only colored his locks but trained them into swooping volutes that he then waxed and pomaded to lacquered immobility.

Without the pompadour, no Elvis costume can be considered complete. Impersonators would never consider going without Elvis’s patent leather coiffure. Austin Butler’s hair in Mr. Luhrmann’s film is shoe-blacked just as Elvis’s was. What each has in common with the other is hair that in its natural state is some shade of blonde.

In civilian life, and as his income grew, Elvis became an early adopter of fashions. Like many hipsters and countless musicians of the late 1950s, he favored Cuban-collared shirts, wide-legged, pleated trousers, slip-on loafers and blouson jackets — a style that men’s wear labels like Prada revisit with clocklike regularity.

Unlike millions of other Americans then and now, Elvis seldom wore jeans outside of the films he starred in once Hollywood discovered the handsome working class Southern hero and put him to work making 31 movies in 13 years. Elvis disliked denim, it was said, because it was too sharp a reminder of his humble origins.

Because Elvis was in certain ways less an innovator than a force magnifier, it seems like a stretch to credit him, as many do, with originating trends for floral print aloha shirts (which enjoyed a vogue after the release of his 1961 film “Blue Hawaii”) or skintight cowhide suits, like the black leather one he wore for a 1968 television comeback special, or a rockabilly style already well entrenched among fans of the rural subculture by the time he came to fame.

Yet for anyone tracing the lineage of men’s wear styles, whether for snap-button Western shirts, winkle-picker shoes, argyle socks, penny loafers or quiffs, Elvis is inevitably there in the pedigree.

Is it perverse to find magnificence in the most parodied element of Elvis’s style evolution? That is, his famous jumpsuits, the costume default of impersonators and trick-or-treaters on Halloween. Typically treated as sartorial jokes, these jumpsuits emblematize the star at his apogee, that moment before his fame and his life collapsed on him and he crumpled to earth. Those glittering garments with their embroideries and nailhead patterns or paste gem barnacles were precursors to the stage-wear worn by every pop star — Prince, David Bowie, Harry Styles — who ever invited his fans to feast their eyes on him erotically.

Oddly, at their core, the one-piece unisex garments were a practical solution devised by Bill Belew, Elvis’s costume designer, to allow him to move freely onstage while maintaining his silhouette. The standup collars, like the lace neck ruffs on a Spanish infanta in a Velázquez portrait, not only framed Elvis’s classical profile, but also seemed to hold up his noble head.

They did something else, though. Dressed in those jumpsuits, Elvis not only cemented an image destined to endure far beyond that of any other pop star but rendered him a near divinity.

If proof is needed, just watch the final concert, in 1977. Though puffy and paunchy, short of breath and with sweat rivulets streaking a face stuccoed with pancake, his trademark hairdo stiff as a wig, Elvis nevertheless rouses himself from a lackluster opening number to achieve a state resembling exaltation.

Dressed in his white Mexican Sundial suit, bedecked front and back with an image of the Aztec sunstone depicting five consecutive worlds of the sun, Elvis moves slowly across the stage like a sacred idol, trailed by a stage hand with a bundle of snowy white scarves draped across one arm. One by one, the helper hands them to Elvis, who drapes each briefly around his neck for consecration before tossing it to eager supplicants.

At this point Elvis has surpassed the limits of fashion and stardom. And, while very soon he would be dead, at this precise moment Elvis Presley was apotheosized.